In November, a previously healthy 63-year old man was transferred by air ambulance to Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) with a diagnosis of sleeping sickness – East African Trypanosomiasis.

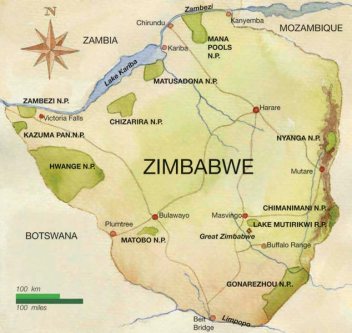

He was a Canadian resident who had travelled to Johannesburg, South Africa for a 2- week business trip in October. At the end of his trip, he went on a 1-week safari holiday to Zimbabwe at the Mana Pools National Park along the Zambezi river.

He recalled multiple painful tsetse fly bites during the safari drives but was otherwise well.

On the way back to Canada, he had a stopover in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Two days after arrival to Brazil, 6 days after leaving his safari in Zimbabwe, he began to feel unwell and presented to hospital with headache, diaphoresis and cervical myalgia.

On presentation he was febrile and had a 2×5 cm indurated, erythematous skin lesion at the site of a previous tsetse fly bite on his right flank. His physical examination was otherwise normal without any other rash, lymphadenopathy, neck stiffness, or neurological findings.

Blood films, examined for malaria parasites by microscopy, revealed trypomastigotes (Figure 1). In Brazil, the finding of trypomastigotes is usually diagnostic of acute Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis). However, based on his recent travel to Zimbabwe, and the morphology of the parasites, he was diagnosed with East African trypanosomiasis.

To stage the disease and rule out central nervous system (CNS) involvement he underwent lumbar puncture. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination documented less than 8 white cells per ml and no parasites were seen in CSF.

Given his history and the positive blood smear, the diagnosis of stage 1 East African Trypanosomiasis was made shortly after his presentation, and, that same day, he started treatment with pentamidine, administered 4mg/kg intravenously every 24 hours.

The following day, repeat blood film examination was negative. Treatment with pentamidine was continued and his symptoms began to gradually improve. After 6 days of treatment in Sao Paulo he was transferred to VGH were he completed an additional 4 days of intravenous pentamidine prior to discharge.

Repeat CSF examinations at months 3 and 6 following treatment both documented only 2 white cells and no trypanosomes. At follow-up 2 years after treatment he was feeling completely well without any residual symptoms.

Discussion

Human African Trypanosomiasis

Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) is a neglected tropical disease. It occurs in focal geographic areas, receives little international concern, and disproportionately affects people who are poor and marginalized.

The following table outlines the key similarities and differences between West and East African Trypanosomiasis.

Cases in Returning Travellers

In 2012, Simarro and colleagues from the WHO published a case series of 94 cases of HAT diagnosed in non-endemic countries (primarily in Europe and United States).

East African Trypanosomiasis (T. rhodesiense or R-HAT) accounted for 72% and occurred mainly in tourists after short visits to Africa. The majority presented acutely unwell in the early (hemolymphatic) stage of illness. Initial misdiagnosis as malaria or rickettsial infection was frequent.

In contrast, case of West African Trypanosomiasis (T. gambiense or G-HAT) occured mainly in expatriates, refugees, or immigrants who had been living in endemic countries for long periods of time. The majority were in second stage, had CNS involvement, and the diagnosis was usually made months after their initial presentation.

The following figure illustrates the difference in epidemiology of the 2 types of Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) in travellers compared with residents of Africa. The numbers represent numbers of cases among travellers, whereas the colours represent the background prevalence of HAT in the local population.

The following figure illustrates a recent trend of increased cases of East African Trypanosomiasis diagnosed among returned travellers in non-endemic settings.

Final point:

An interesting point illustrated by the patient in the case presentation is that he did very well following treatment with pentamidine.

Although pentamidine quickly replaced suramin for the treatment of stage 1 West African Trypanosomiasis, suramin has remained the standard treatment for stage 1 East African Trypanosomiasis in endemic countries and is listed as first line for the stage 1 East African Trypanosomiasis by both the WHO and the US CDC. Some reviews and guidelines do not even list pentamidine as a treatment option for stage 1 East African Trypanosomiasis.

However, there is actually very limited evidence to support the preference of suramin over pentamidine for the treatment of East African Trypanosomiasis. There has never been a controlled clinical trial to compare the two drugs. In a non-randomized case series in Mozambique favourable clinical responses were documented in 61% of patients treated with suramin vs 74% of patients treated with pentamidine.

As well as our case, there have been several other reports of patients with first stage East African Trypansomiasis treated outside of endemic countries with pentamidine that have documented good clinical response, including a case of a man with critical illness and very high parasitemia treated in Poland.

Although pentamidine carries risks of hypoglycemia and rarely pancreatitis, compared to suramin, it has a favourable side effect profile, is more readily available, and is easier to administer.

Given the available evidence, pentamidine deserves further consideration for use in the treatment of East African Trypanosomiasis.